ST.Alan Jackson’s voice wavered the moment he appeared on camera — softer, slower, carrying the weight of a husband holding onto hope. In a raw and emotional update, Jackson shared new details about his wife’s condition, while thanking fans for the overwhelming wave of love and prayers that have poured in from every corner of the world.

Alan Jackson’s Heartfelt Update Touches Millions: A Husband’s Hope Amid Uncertainty

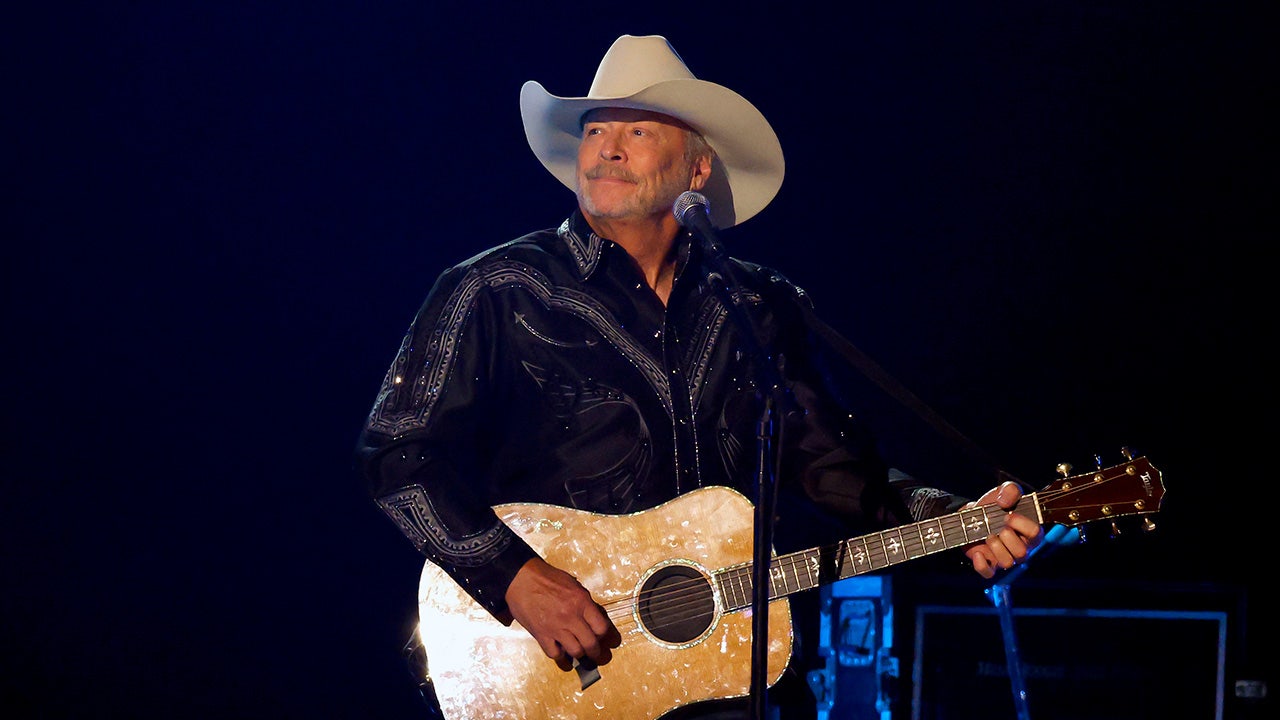

In a moment that has captured the hearts of country music fans worldwide, Alan Jackson recently appeared on camera in a raw, emotional video update. The country legend’s voice wavered noticeably— softer and slower than the commanding baritone that has defined hits like “Chattahoochee” and “It’s Five O’Clock Somewhere.” It was clear he was speaking not as the iconic performer who has sold over 75 million records, but as a devoted husband clinging to hope during a challenging time for his family.

The update focused on the health of his wife, Denise Jackson, his high school sweetheart and partner of over 45 years. While Alan did not delve into specific medical details in the brief clip, his demeanor spoke volumes. He shared new insights into her ongoing condition, expressing gratitude for the global outpouring of support while promising to keep fans informed. Viewers described the scene as profoundly intimate, with Jackson pausing several times to compose himself, his eyes reflecting a mix of vulnerability and resolve.

Jackson emphasized how deeply moved he and Denise have been by the kindness from strangers. “The messages, the prayers, the personal stories you’ve shared—they’ve meant more than words could ever express,” he said, his voice cracking with emotion. Fans from every corner of the world have flooded social media, email inboxes, and even the couple’s official channels with encouragement, sharing their own experiences of love, loss, and resilience. Fellow artists, including longtime peers in the country music community, quickly joined the chorus of support, posting tributes and prayers.

At the end of the update, Jackson leaned closer to the camera and whispered a tender promise meant solely for Denise—a quiet vow of enduring love that has left viewers in tears. Though the words were soft, they resonated powerfully, reminding everyone of the profound bond that has anchored the Jacksons through decades of triumphs and trials.

Alan and Denise’s love story began in the small town of Newnan, Georgia, where they met as teenagers at a local Dairy Queen. Alan famously tossed a penny down Denise’s shirt as a playful icebreaker, sparking a romance that led to their marriage on December 15, 1979. Over the years, they’ve navigated the highs of Alan’s meteoric rise to stardom—induction into the Country Music Hall of Fame, countless No. 1 hits, and Grammy awards—alongside personal challenges that tested their commitment.

Their journey hasn’t been without storms. In the late 1990s, the couple briefly separated amid the pressures of fame, but reconciled stronger than ever, renewing their vows and drawing closer through faith and counseling. Denise later chronicled this period in her bestselling book It’s All About Him: Finding the Heart of My Life, offering inspiration to others facing marital struggles.

Health scares have also marked their path. In 2010, Denise was diagnosed with colorectal cancer, a shock that brought the meaning of “in sickness and in health” into sharp focus. Alan stood by her side through chemotherapy and radiation, and she emerged cancer-free after intense treatment. The experience shifted their priorities, leading them to simplify their lives and cherish family time more deeply.

More recently, Alan has been open about his own battle with Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (CMT), a hereditary neurological condition that affects mobility and balance. Diagnosed over a decade ago, it has progressively impacted his ability to perform, prompting him to announce his “Last Call: One More for the Road” tour as a farewell to live shows. He wrapped most dates in 2025, with emotional performances that often included tributes to Denise, such as inviting her onstage for slow dances to their song “Remember When.”

Through it all, Denise has been Alan’s unwavering rock. In public appearances, like the 2025 ACM Awards where Alan received a lifetime achievement honor, he tearfully credited her as his “best friend since I was 17.” Their three daughters—Mattie, Alexandra (Ali), and Dani Grace—have grown into accomplished women, blessing the couple with grandchildren and adding layers of joy to their family life.

The latest update has sparked an immediate wave of compassion across social media. Hashtags like #PrayersForDenise and #AlanJacksonFamily trended as fans shared stories of how the couple’s music and resilience have soundtracked their own lives. One fan wrote, “Alan and Denise’s love is the real deal—the kind that inspires songs and survives everything.” Another added, “Seeing him so vulnerable reminds us these legends are human, facing the same fears we all do.”

Fellow country stars echoed the sentiment. Artists who have shared stages with Jackson over the years posted messages of solidarity, emphasizing the tight-knit community’s support during tough times. “The Jackson family is in our hearts,” one prominent singer noted.

This moment underscores the unique bond between country artists and their audiences. Jackson’s traditional honky-tonk style has always felt personal, drawing from real-life joys and heartaches. Songs like “Livin’ on Love” and “Remember When” mirror his own marriage, making fans feel invested in his story.

As the Jacksons face this chapter, Alan’s promise to keep everyone updated offers a thread of connection. In an era of fleeting celebrity news, their authenticity stands out—a reminder of enduring love, faith, and gratitude.

The whispered words at the video’s close, though private, have become a symbol of hope for many. In them, fans hear an echo of the vows exchanged decades ago: a commitment to stand together, no matter what. Tonight, hearts are breaking not from despair, but from the beauty of a love that refuses to fade.

The outpouring continues, a testament to the impact Alan and Denise have had. As one supporter put it, “Your music healed us; now let our prayers heal you.” In this fragile yet hopeful time, the world waits with the Jacksons, holding onto the same quiet promise of tomorrow.